This guide covers a variety of Circassian music while also highlighting some of the outstanding traditional and experimental artists in this field. These directions include music rooted in folk which is preserved on the margins or even outside the industry; contemporary classic; post-soviet estrada; turbo-folk that one can usually hear in tourist cafes and modern interpretations of traditional music ranging from Nordic influences to atmospheric black metal.

Circassians (called Adyghe people) are one of the Northern Caucasus ethnicities. In 1864 almost half a century Russian-Caucasus war ended with the region being colonized. Most Circassians either died or were departed to Ottoman Empire. From that territory they started to settle in Syria, Jordan and others.

“Such hermetic and self-sufficient tradition in the diaspora lets music be well preserved, but slows down emerging of new ideas and directions.”

Up to the second half of the XX century traditional music remained as an inherent part of daily life, yet to be exoticized or regarded as a legacy to preserve. There was no opposition between folk and ‘contemporary’ music, so professional musicians called Djeguako (The Players/Performers) were both moving forward established genres and developing the new sound. While being oriented towards existing within the community, it was artists who gained access to recording who prospered and saw a wider audience.

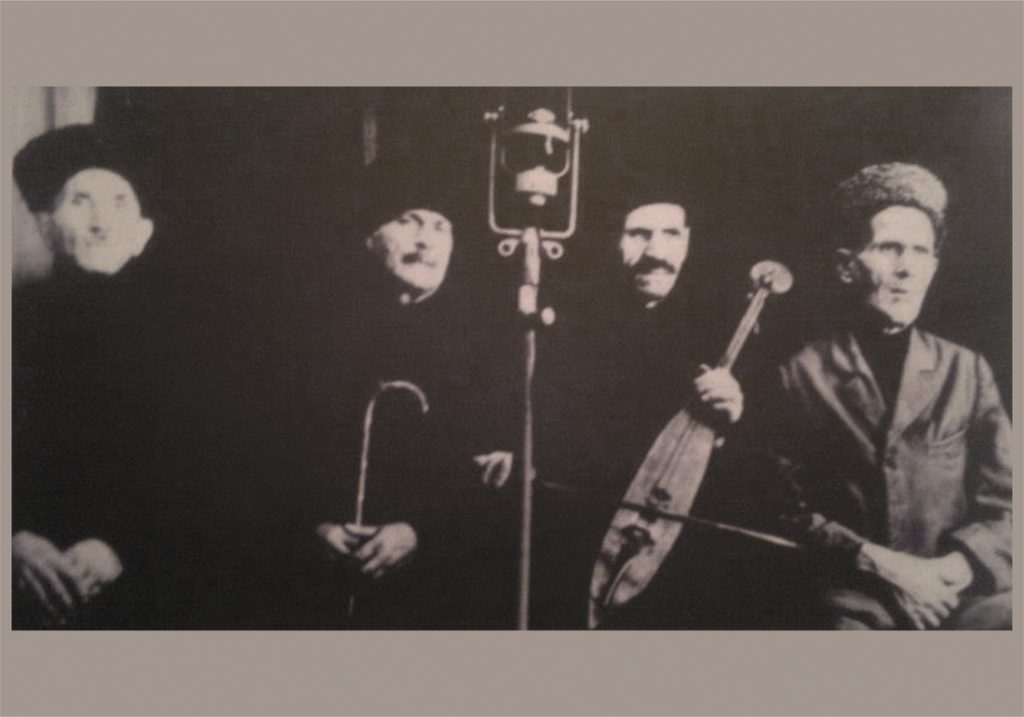

Magament Khagaudzh from Adygea was active from the middle of XIX till the beginning of XX century. He became the symbol of ‘authentic’ Adyghe music largely due to the recordings with an ensemble made in 1911-1913 by UK Gramophone Company. These turned into the first Circassian music documentation and also the standard of how it sounds. He was at the same time the keeper of the tradition and innovator whose improvisations became classic.

There were other recognized djeguako in USSR whose biographies became a part of folklore, but rarely someone listens to them except folk historians. The power of global changes and Soviet unification made traditional music move outside from daily life and crafts into museums under ‘sounds of the distant past’ labels. Djeguako were replaced by trained singers and composers while traditional festivities with music accompanying them were turned into formal concerts.

Traditional performers could not fit the new system. Government segregated them into the niche of folklore arts festivals. But such official festivals reduced rich music tradition even further — they demanded the post-card aesthetic to represent the gallery of acceptable ethnicities of all Soviet republic. But the raw sound was the feature of traditional music, it was not tailored to official stage cliches and therefore deviated from its paradigm.

Since then djeguako and those who innovate within tradition almost vanished and found themselves in the compelled underground.

Authentic Underground

These are mostly musicians of the older generation who know traditional songs directly from their families and artists of the past who they witnessed in person. They perform Circassian music without refreshing it in any way as they are the last keepers of their ancestors’ legacy. Some do not see themselves as ‘real’ musicians because they are not conventionally trained and even feel ashamed because of it. And others, especially young folk-performers are against being viewed as musicians due to their contempt for the official scene. Countless performers like this are not visible beyond family circle and do not have albums or videos (except Instagram stories which Caucasian people are very fond of).

One of the most influential, yet paradoxically little-known musicians from underground is Aslanbech Chich from Adygea. While most traditional artists there decided harmonica to be a national brand instrument and honed skills with it, Chich stayed faithful to nearly forgotten shichepshin. This is a violin with usually two or three strings which was used for the majority of Circassian music until the middle of the XX century. Chich didn’t persuade fame and recognition, his natural environment was gatherings with friends and performing for them in the style he inherited from elders.

These are mostly musicians of the older generation who know traditional songs directly from their families and artists of the past who they witnessed in person. They perform Circassian music without refreshing it in any way as they are the last keepers of their ancestors’ legacy. Some do not see themselves as ‘real’ musicians because they are not conventionally trained and even feel ashamed because of it. And others, especially young folk-performers are against being viewed as musicians due to their contempt for the official scene. Countless performers like this are not visible beyond family circle and do not have albums or videos (except Instagram stories which Caucasian people are very fond of).

One of the most influential, yet paradoxically little-known musicians from underground is Aslanbech Chich from Adygea. While most traditional artists there decided harmonica to be a national brand instrument and honed skills with it, Chich stayed faithful to nearly forgotten shichepshin. This is a violin with usually two or three strings which was used for the majority of Circassian music until the middle of the XX century. Chich didn’t persuade fame and recognition, his natural environment was gatherings with friends and performing for them in the style he inherited from elders.

Aslanbech Chich would remain as the unrecognized genius of old music who didn’t conform to modern times if not for another enthusiast of Circassian music, Zamudin Guchev. He moved from Kabardino-Balkaria to Adygea because in the 1970’s it was seen as an oasis for traditional culture. The acquaintance with Chich defined the path of Zamudin since then. ‘Chich was a virtuoso, his performances were stunning — they were both easy and fascinating to listen to. Though he lacked any teaching capacities. The master could not communicate nuances of what he does and to pass it to others.’ Eventually Zamudin started not only singing and playing shichepshin, but also craft instruments himself. Since 1980’s he has taught children and teens all facets of traditional music including collective performing, instruments making, Adyghe ethics and aesthetics. His main project is an Ensemble Of Traditional Singinging And Instrumental Music Жъыу (Zhyu/Jiu) which performs songs from archives as close to the original as possible.

Жъыу was not a regular ensemble, rather an artistic community or music residency. Its members carried this experience to create their own centres for folk-music and gathered into new ensembles while frequently rejoining as Жъыу. By 2012-15 Жъыу are at the forefront of Circassian underground. Though their popularity is not on par with mainstream singers, their influence on small and loyal audiences was immense. Adyghe traditional instruments and songs could be now heard everywhere among Circassians. Most contemporary musicians are either trained by Zamudin or at least were inspired by his numerous projects. One of the prominent Жъыу members is Zaur Nagoev (Nagoy) — a charismatic singer, instrumentalist and kind of a rock star of Circassian traditional music. Zaur went beyond the reconstructionist approach to archival recordings and developed a unique singing and performing style. This gained him credit for modern jeguako. Discovered and recorded by Ored Recordings, Zaur Nagoev becomes a notable part of Russian independent scene making appearances at Moscow new and experimental music festivals pushing his performance to some place between concert and folk stand up.

In Turkey, which officially counts more Circassians than in their historical habitat, musicians started to think about going on stage, tv and recognition among wider public just recently. Adyghe performers in Turkey play music exclusively within their community. That’s why it still naturally intertwines with daily routine and has no need to be artificially reconstructed. While Circassian weddings in the Caucasus of the last twenty years look as a huge dinner with invited pop-stars, in Turkey people still arrange traditional festivities where food is far from leading the process. Harmonica is played several hours straight, and dancers, singers and percussionists are the same people. So in diaspora the performance of traditional music is less of a concert and more of a ritual and celebration.

For Anatolian Circassians performing music signifies their national and cultural identity, a way of resisting the assimilation. Being isolated for a long time, Circassian music in Turkey has transformed into a new dialect drifting away from Caucasus origins. Adyghe people were consciously avoiding Turkish, Kurd and Laz influences. That is why one won’t find in Adyghe music popular instruments of that region — saz, bağlama, zûrna. They mostly play German Hohner diatonic harmonica and use пхацыч (pkhatzych – ratchets) as the only percussion.

Besides harmonica, Guchev’s impact on Turkish diaspora can be seen in more frequent application of shichepshin.

A unique Circassian style was also formed in Syria and Jordan, gaining a lot from classic Arab music. And as in Turkey, Circassian music in those places was developed as a dance genre. One outstanding feature of Jordan and Syrian styles are that even ritual melodies for festivities sound calm and contemplative. Such hermetic and self-sufficient tradition in the diaspora lets music be well preserved, but slows down emerging of new ideas and directions. The latter starts to be imported from history which can eventually lead to standardizing of all Circassian music.

Soviet Tradition

Soviet cultural politics on the republic territories and its ethnicities (even Russians themselves) can be called colonial. So traditional music was regarded as a peculiar exotic leftover of the pre-civilized era. It was promoted that the USSR brought education, science and cultures to them all. The new ‘modified’ folklore was presented as truly professional by being reworked by trained composers and performers.

Such approach extremely diminished ‘home’ folk music status and created questionable hierarchy. Though Soviet period brought its own original music. Despite it being brought from top and depended on political conjuncture many musicians at the time believed in Soviet project and were sincere about their art.

Zaramuk Kardangushev from Kabardino-Balkaria was one of those who merged academic singing, professional choir and Circassian heroic songs. Between 1950 and 1980, he made numerous expeditions to collect immense archives of ethnographic recordings. He also worked at the republican radio where he produced shows about folklore and put his field recordings on. Zaramuk can be called the Circassian Alan Lomax — it was him who shared for many their own traditional music. Zaramuk’s influence is so vast that his academic style became standard which was mimicked even by rural performers of the older generation. While he became a hero who popularized traditional music, his overshadowing of non-academic old song styles must be kept in mind.

There were also collectives inspired by experiments of Russian composers in the end of XIX — the beginning of XX century such as Balakirev, Avraamov, Prokofiev and others. Circassian masters unified orchestral language with tradition which they justified as a musical evolution and ‘raising folklore music to the heights of world art’.

‘Folklore material is merely a basis for our art while technical and artistic proficiency are necessary to carry it to the modern listener. All the civilized world makes an accent on professionalism’ — said Leonid Bekulov, a founder of Бжьамий (Bjamiy) ensemble from Nalchik. While it sounds naïve and controversial, sound-wise Бжьамий was revolutionary. Musicians were equally profound in the traditional material and European instrumentalism, creating Circassian chamber neoclassic. In the 1980’s they toured in France and published a record on European label. This was considered as their peak, gaining cult status and confirming the orientation to success not within the community, but among a wider audience.

Formally Бжьамий still exists — musicians rehearse and sometimes perform. But current government support cannot be compared to Soviet which degrades enthusiasm of those innovators — Umar Thabisimov with Adyghe romance songs, Vladimir Baragunov with epic symphonies and Djabrail Khaupa — one of the main Circassian academic melodists.

Turbo-folk

After the collapse of Soviet Empire and its cultural institutions professional Circassian music started to perish. Composers and ensemble directors who were used to the government support could not adapt to the new order which was the lack of order. Their place was taken by pop music with folklore elements — Circassian turbo-folk as a parallel to Balkan quasi-folk. These few could break through Soviet corpses and rise from the bottom.

The most memorable (and financially successful) of them is singer Cherim Nakhushev. In the 1980’s, Nakhushev was still continuing Soviet tradition and performed epic songs with Kardangushev on Kabardino-Balkarian TV. He changed his style in the 1990’s, still remains an icon of Circassian pop. Songs of that period feature lyrics about love, Adyghe way of life, mother and such noble values. They were all performed in the folk-pop manner of post-Soviet estrada. Nakhushev is following an image of the polite and obedient guy, who will be definitely in favor among your mother and grandma.

Though less saccharine, but equally pompous, Circassian pop is produced in Turkey by Kushhov Dogan. Like Cherim, he implements traditional themes and authors into run-of-the-mill pop tunes. The latest and glaring pop artist in this wave is Magamet Dzybov from Adygea, whose style can be traced back to Khagaudzh and late Soviet Circassian chanson which was formed on the base of Adyghe songs and Southern Caucasus criminal ballads.

The difference between turbo-folk and traditional music is in arrangement and production styles. So home recordings by Magomet can be defined as music ethnography while most concerts are estrada.

Turbo-folk is the most commercially sustainable phenomenon in contemporary Circassian music. At the same time it is almost unknown outside Adygea. The exceptions are songs in Russian language which Dzybov also has. This music wouldn’t fit even the most varied catalogues like Sublime Frequencies. It sounds too slick and polished with sanitized professionalism instead of passion.

Post-traditional Music

The first experiments in attempt to reinterpret Circassian traditional music in a more experimental way were done in the 1990’s. One of them is a collaboration between composer and arranger Aslan Gotov with a band Oshten from Adygea. This project had promising ideas and eclectic sound when Russian-Caucasus war songs mutated into hard-rock, almost hardcore. And ritual songs evolved into the first and last cases of Circassian new wave.

In the 2000-10’s several bands went on synthesizing traditional melodies with Western production. It frequently resulted in some analogues or even imitations of Deep Forest, Enigma and other commercial ‘world/new age’. Khagaudzh Ensemble were one of pioneers who consciously referred to experimental forms. It started as a collaboration between musician Tembolat Tkhakshloko from Nalchik and Timur Kodzokov of Ored Recordings. Initial idea was resurrection of lesser known styles of Circassian music — almost extinct mandolin playing, traditional chamber ensembles and others. They attempted to develop their original sound within canon.

Khagaudzh Ensemble along with Ored Recordings toured several contemporary music festivals and recorded an album. Then an internal artistic conflict has grown obvious by 2018 — Tembolat was more engaged with studio experiments and electronics while Timur continued the initial direction. Thus Khagaudzh transformed into Hagauj and went its own way recording three albums. The latest, Electronic Tradition, puts together authentic instruments and sifts them through effects on top of electronic beats. Audio and visual aesthetics of Hagauj showcases heavy influence of Scandinavians like Wardruna and tends toward a darker side.

Part of those who separated from Khagaudzh continued their search of signature sound and expand on it by working with field recordings and acoustic instruments. This led to the creation of Jrpjej project which is usually 4 to 7 musicians. Timur Kodzokov lays foundation with sound production, arrangements and performing strings. Other musicians bring their own personality, style and techniques. It is notable that all Jrpjej members came to traditional music against common paths. They were all raised within western pop, rock and experimental context and started to explore folk much later.

Qorror, the first album by Jrpjej, explores Folk Horror aesthetics in Circassian music. Its sound was influenced by Irish band Lankum, MMMD from Greece and early Norwegian black metal, though there are no direct elements of this music in Qorror.

‘Through Jrpjej I constantly expressed my love of black metal. If one listens closely to my parts with traditional instruments, it is easy to hear the technique of early Burzum and Mayhem circa De Mysteries Dom Sathanas. I tried to adapt it for Jrpjej sound, but then an insight happened, why should I mask it under some disguise, I can do myself black metal in a way I feel organic myself, says Timur Kodzokov. Thus Zafaq was born and became the most radical and ambiguous Circassian project. Kodzokov put shichepshin and apapshin away, took electric guitar with pedals and invited Amar Abazov, a drummer from Nalchik who was known for his deathcore band Awake For Life.

Zafaq performs ritual songs of casting the rain, extracting the bullet, pagan dances and epic songs with giving them old-school black metal interpretation style. ‘We wanted to avoid pretentiousness and melodics of folk metal which are usual results of such synthesis. This stereotyped approach seems boring and blunt to us. So we decided to go into a raw atmospheric direction, where ‘Circassian’ would be the essence of music rather than some of its parts’.

—

*translated from Russian by Nikita Rasskazov.

WRITTEN BY:

Bulat Khalilov

Source : theatticmag.com